360 room projection in Villa Bienert at Dresden

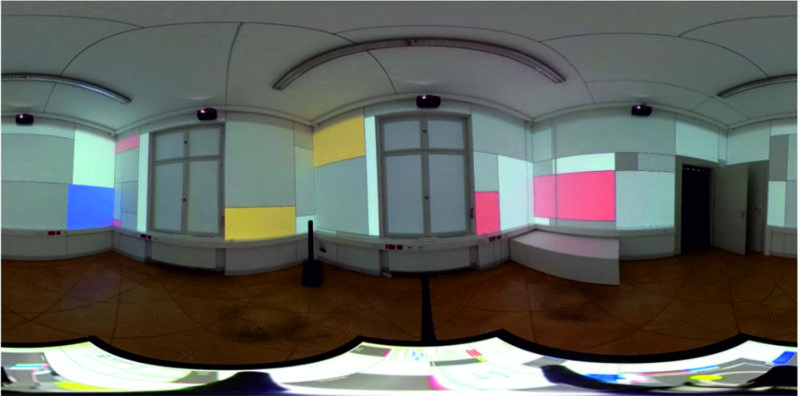

Bienert’s Villa in Würzburger Straße 46 at Dresden, for Mondrian provided his room design, has survived dramatic historical change largely unaltered (Wagner, 2019) – offering a unique opportunity to render the plan in the actual space it was meant to fill. The research institution Barkhausen Institut commissioned an installation to Intolight, an agency for interactive installations, to revive Mondrian’s design as 360 deg video installation in its intended space, the surviving Villa Bienert. Any attempt to demonstrate the Ida Bienert’s ‘Damenzimmer’ could have looked like, how, would be facing various challenges. The room has seen several renovation phases, such as the installation of power sockets and cables covered by surface ducts running around all four walls, or covering the floor with wooden parquet at some stage. Moreover, some discrepancies between Mondrian’s design and the physical dimensions of the ‘Damenzimmer’ would require small adjustments to the boundaries between colour fields (Zanker et al, 2019).

Other limitations to a full 360° video designers in such a small space arise from parts of surfaces being obstructed by the equipment, and projectors not reaching the full extent of space, thus limiting the ‘ecologic validity’ for the study of aesthetics questions. With the free adoption of the historical concept in a 360° room projection, this commission illustrates the focus of their research topics related technology questions: The straight lines, pure forms and colours of abstract painting are used to demonstrate a different kind of network: the Internet of Things and its technical challenges. In other words, the room turns into a data channel that opens possibilities to visualize some technical challenges addressed by the Barkhausen Institut. Allowing the users to play with Mondrian´s sketch and change its appearance, can demonstrate effects of interference factors in the communication between wireless transmitters and receivers, case of packet loss rate, or a privacy intrusion.

As a result of these constraints, the video projection of Mondrian’s plan a installed by ‘Intolight’ was restricted to the walls between the electric ducts and the ceiling, and blinded windows. Their main aim was not focused on arts historical accuracy but on the intention to appropriate his design to create an interactive installation that would allow visitors to explore the abstract relationship between cardinal lines, pure shapes, and basic colours. To enhance this experience, the room was filled with music, and a white console was installed at the centre of the room that would allow visitors to change the appearance of the room by increasing the number of rectangles or colour of shapes.

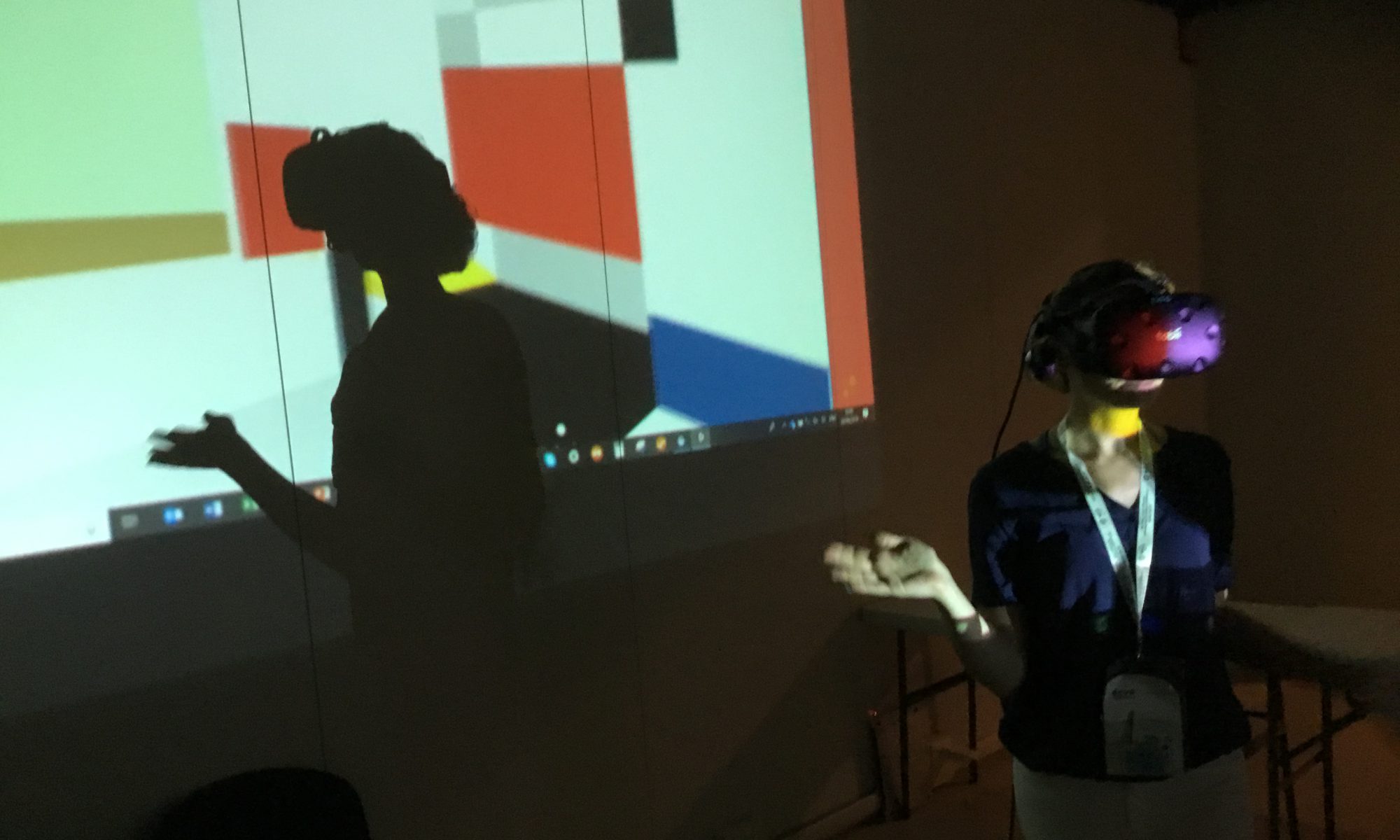

Making use of this unique opportunity to work in the original ‘Damenzimmer’, our team did run an explorative eye-tracking experiment during the public presentation of the ‘Intolight’ installation, to compare gaze patterns ‘on-location of the real Mondrian Salon’ with those in the Salon recreated by Zobernig in the museum, as well as inside the VR environment.

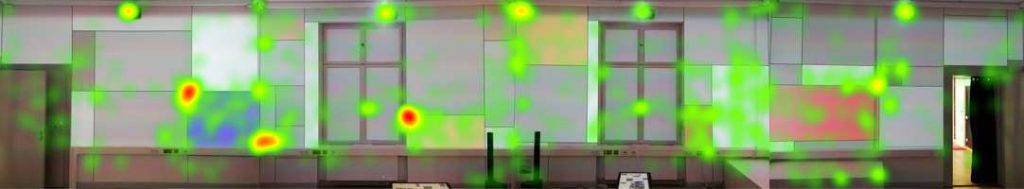

The concept of an interactive installation, however, was difficult to reconcile with the ideal of a controlled experiment – including a reassurance that every participant would be exposed to the same room design. The emission, occlusion and reflection of light – it’s hardly predictable saturation, hue and lightness – together with the enriched sound scape, certainly would make a rather different experience drawing visitors attention – and foot fall as much as eye movements – away from the patterns on the walls, fundamentally changing the interaction between visitor and environment. Therefore a comparison between the ‘Damenzimmer’, ‘Zobernig’, and VR space would be superficial if not futile. Still, it is interesting to speculate whether there could be characteristic feature combinations (such as lone intersections with contracting colour) that might preferentially attract first fixations, irrespective of unpredictable overall patterns. An initial average heat map form 3 participant who produced a sufficiently long recording in the 360° room projection is shown in the figure below. There seems to be a tendency to look at the blue and red square and in particular intersections, which might be different from the behaviour in the real and VR room installations in the museum that displayed stronger grey-level contrasts.

References

Wagner, Mathias (2019). „Aber für Zimmer dieser Art muß man sich auch andere Menschen denken!“ – Piet Mandirans Raum für Ida Bienert‘, In „Zukunftsräume: Kandinsky, Mondrian, Lissitzky und Grüße die abstrakt-konstruktive Avantgarde in Dresden 1919 bis 1932“ Sandstein Verlag, Dresden.

ZZanker, J.M., Gulhan, D., Stevanov, J. Holmes, T. (2019). Constructing Piet Mondrian’s design of a ‘Salon for Ida Bienert’; in: Perception Vol. 48(2S), 42nd European Conference on Visual Perception (ECVP) 2019 Leuven, p 98-99