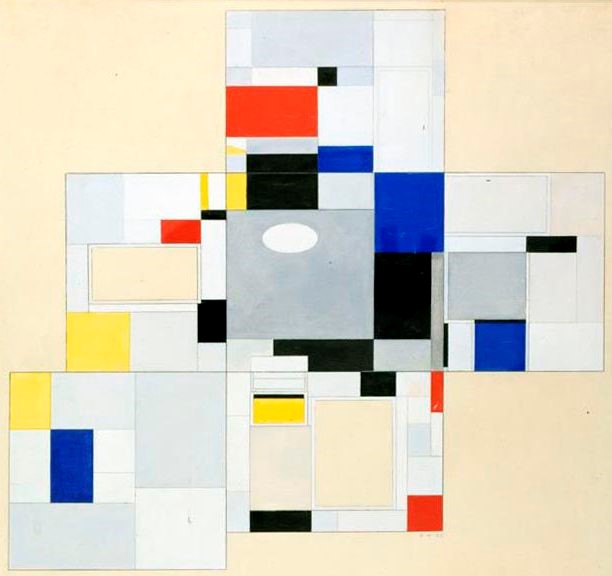

Piet Mondrian, the most prominent member of the Dutch ‘De Stijl’ arts movement who created some of the iconic paintings of abstract art (Joosten, 1998) was commissioned by Ida Bienert in 1926 to design a room in his idiosyncratic style of horizontal, vertical lines and rectangles filled in white, grey, black and primary colours that follow composition rules of ‘De Stijl’ aesthetics where shapes and colours are in perfect balance (see figure). The reasons why this room was never realised has been discussed by experts over many decades (Troy, 1980), and there were three attempts to reconstruct this room at full scale in international galleries (Holtzman & James, 1970) – which however were met with criticism about their realisation, and were generally regarded of limited success. We argued previously (Stevanov & Zanker, 2017) that one reason why Mondrian did not realise his design could have been that Mondrian patterns in a 3D space diverged from the key principles of ‘De Stijl’ aesthetics (Mondrian, 1920) due to conflicts with the rules of perspective.

Piet Mondrian’s design for a ‘Salon de Madame B… à Dresden’, 1926 – the ‘Damenzimmer’ ; Image source: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany.

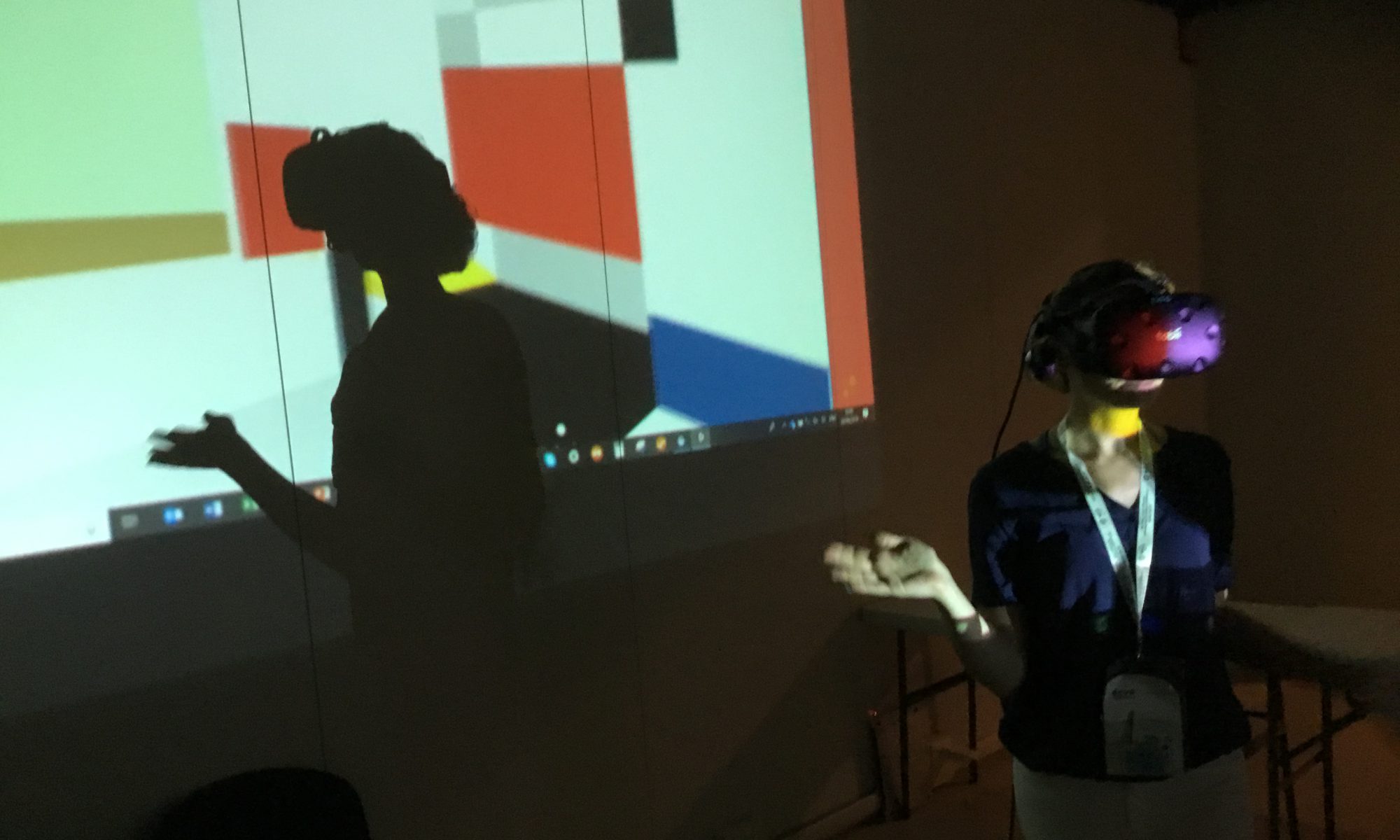

From vision science we learned that corners of a room are mapped as oblique lines that do not maintain orthogonal intersections in retinal image – such non-orthogonal intersections are inconsistent with Mondrian’s dogmatic demand for pure aesthetics. Due to automatic perceptual mechanisms of shape constancy and depth perception, however, the retinal image is interpreted differently in the visual cortex. Oblique retinal lines are perceived as boundaries of rectangular shapes in depth whereas corners are perceived as T-junctions rather than Y-junctions of retinal maps. For the purpose of demonstration, we first reconstructed the salon as a Computer Graphics (CG) model in animations (see figure) that allowed a range of viewing distances, showing what an observer would see when standing inside or outside of the salon (with the wall closest to the observer being removed). However, seeing an animation doesn’t bring immersive and authentic experience of walking into the Salon.

References

Holtzman, Harry, & James, Martin S. (1970). Mondrian: The process works (Martin S James & Harry Holtzman Eds.). New York: Pace Gallery.

Joosten, Joop M. . (1998). Catalogue Raisionnė of the Work of 1911 – 1944. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publisher.

Mondrian, Piet. (1920). Neo-Plasticism: the general principle of plastic equivalence The New Art – the New Life: the Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian (James, Martin Holtzman, Harry ed., pp. 134-147). New York: Da Capo Press.

Stevanov, Jasmina, & Zanker, Johannes M. (2017). Exploring Mondrian Compositions in Three-dimensional Space. Leonardo, 1-11. doi:10.1162/LEON_a_01583

Troy, Nancy J. (1980). Mondrian’s Designs for the Salon de Madame B…, à Dresden. The Art Bulletin, 62(4), 640-647.